A collaborative effort between researchers from DESY, the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Chalmers University in Sweden and the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland has yielded a cutting-edge multimodal imaging approach to investigate breast cancer tissue. With the help of this technique, researchers can simultaneously extract information about the nanostructure of the tumor and quantify the chemical elements present in a millimeter-scale sample in all three dimensions. A unique combination of research possibilities at PETRA III and new analysis methods enables this high level of detail.

Breast cancer caused 685 000 deaths globally in 2020 according to the WHO. It is not life-threatening in its earliest form. But if the cancer cells are able to spread further in the tissue to nearby lymph nodes or important organs, this metastasis can be fatal. In a recent pilot study published in Nature Scientific Reports, the team applied this revolutionary imaging approach to a breast cancer sample. The results show how key molecules collectively influence the metastatic mechanism. This breakthrough paves the way for an in-depth investigation of breast cancer metastasis, promising novel therapeutic approaches and personalised treatment strategies, which could ultimately improve patients’ lives if recognized early enough.

Traditional experimental models often fall short, relying on 2D cell cultures or animal models that do not faithfully replicate the complex physiological patterns of human tumor environments. The multimodal imaging approach presented in this study represents a significant step forward by providing simultaneous nanoscale morphological and physiological information from real samples, thus giving researchers information about the shape and composition of real cancer tissue.

André Conceição, the first author and beamline scientist at the PETRA III SAXSMAT beamline P62, emphasises, “Although demonstrated for breast cancer, this approach’s versatility extends to other organs and diseases.”

The study opens avenues for further exploration of breast cancer metastasis and pre-metastatic niches (PMNs). Advanced X-ray multimodal tomography can generate complementary 3D maps for different breast cancer molecular subtypes. It holds the potential to contribute to the development of more targeted and effective strategies for diagnosis and treatment.

Read more on DESY website

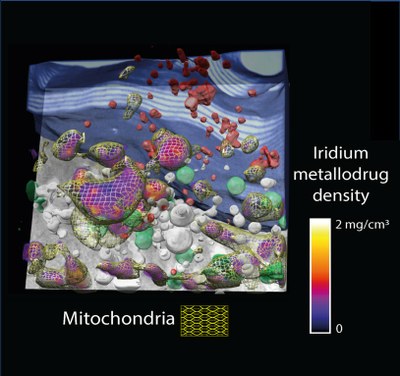

Image: 3D vector field of the collagen direction and degree of orientation obtained by SAXS-Tensor-Tomography